I’ve talked a lot about growing up in an area that was largely full of white people (I believe 98% of the county I grew up in was white during the 80’s). The effect this had on me, growing up, was not actually the one you might expect. Instead of (I thought) teaching me explicitly to be a racist, it taught me that racism was some kind of anomalous thing. I mean, *I* didn’t notice people of color. Everybody was the same to me! Racism was a silly thing that no logical person would ever buy into. It didn’t matter what color anybody was. I treated everyone the same, because it made no difference…. To me. Because I was white. I had the privilege of being able to care – or not – about race, because I was of the “invisible” race in the country, the default.

But like my starry-eyed belief that my gender also made no difference in the way I was perceived in the world, this was a short-lived notion that didn’t last much past my teens. What I started to realize is that it didn’t matter what I thought – there was already an institutionalized system in place, and it was the same system that ensured I grew up in a county that was 98% white.

When my great grandmother died, my great grandfather was showing us some documents from around the same time he bought his house in Portland, OR. This was in the 40’s, I think? I picked up this marketing flyer for the neighborhood that basically said how it was a desirable place to live because buses didn’t go there (read: poor people) and “undesirable” people weren’t allowed to live there (read: non-white people). The area had, of course, grown much more mixed over the years, and as far as my great grandfather was concerned, this was the first step in its demise. I remember him grumbling over the paper, “Things were very different in this neighborhood then. Much better.”

So of course I couldn’t really see segregation, and how it worked, because I was so neatly cut off from people who were different from me. I lived in a place of invisible race, full of white folks. The people I saw everyday were mostly white. At work, at school, at the mall – I just figured this was how it was. Of course race didn’t matter and we were all the same, I told myself, but it’s a lot easier to say that when all the people you see every day look the same way you do, and are the same people making the laws, and setting down the unwritten rules. And deciding where the white and non-white people live.

Because I was a white person growing up in white suburbia, it didn’t really dawn on me how stiffly our country was still segregated until I spent a year and a half living in South Africa. In the US, about 28% of our country is non-white now. In South Africa, over 80% of the country is non-white.

That meant that the way the world was segregated, even post-Apartheid, was glaringly more obvious to me. Most of the world was non-white where I lived, in Durban. It was only when you’d walk into isolated upperclass neighborhoods, or down certain streets, that you saw these little congregations of white people sitting behind their ten-foot barbed-wire topped fences. But even then, everybody had a housekeeper, and a gardener, and a handyman, and those people – in nearly all cases – were not white. So when you walked into a white enclave, it felt exactly like a white enclave should feel: not “normal.” It was abnormal to be in a neighborhood primarily filled with white folks.

I remember the first time I walked into a store in downtown Durban and realized I was the only white person there, just a couple weeks after arriving. It was a startling moment of dissonance. I felt like I’d done something wrong, like maybe I wasn’t supposed to be there. I realized I was 22 years old, and had never in my life been the sole white person… well, anywhere. And the knowledge of that, the striking realization that, in fact, the world I grew up in was a false one, that I had grown up under the false pretense that being white was somehow the norm, and that I had somehow picked up this strange illogical notion that the rest of the world was of course mostly-white too, was absolutely shocking to me. We expect that we’re smarter than that. That knowing something intellectually – of course the world is diverse and varied and wonderful and I had “known” that since I was a child– does not translate into real knowledge of that world until you experience it, was… really depressing, actually. Because I realized how many other white people in America had grown up just like me, in these false white rural and suburban ghettos where they had absolutely no idea of the actual composition of America.

But wait, wait, a lot of other rural/suburban-grown white people might say – this isn’t fucking South Africa. Most people in the US are white! Where I grew up is just a reflection of the country. Everyone really is just like me!

Well, unless 30% of the people you see every day are non-white – no, it’s not.

And here’s why:

It was constructed that way.

It didn’t take long for me to adjust to my initial weirdness over being so white in a place where that wasn’t the norm, of course. It became really normal for the world to *not* be monochrome. It was just life. Life was really vibrant when I lived in Durban. The people were incredibly nice, and the food was amazing. Oh, certainly, there was some terror and madness – the owners of my building hardly ever sprayed for bugs, often forgot to pay their water bill, and it was considered suicidal to go outside alone after dark – but I had a sliver of a view of the Indian Ocean, went to the beach whenever I wanted, and rent was the equivalent of $150 a month. I had a new normal.

After living in Durban for eight months or so, I flew home to visit my family. I had a layover in the Minneapolis airport. I remember sitting there on a bench near the food court, scribbling in a notebook as people streamed by. After about an hour or so, I realized I felt deeply uncomfortable. Something felt very off. Very strange.

I looked up from my notebook and looked at the people streaming by… and realized what the source of my discomfort was.

Everyone was white.

Just as I’d done when I walked into that store where I was the only white person, I felt a moment of dissonance. Well, of course, I told myself – it’s Minnesota. Of course everyone is white here. My brain neatly pushed that “normal” lever, where of course 99% white everything, everywhere is just “normal.”

It wasn’t until I went to the food court to get something to eat that I was reminded of the lie.

Because the people working in the food court?

Were overwhelmingly non-white.

South Africa’s segregation was easier for me to see because it was a foreign country. I could look at it as an outsider, and point at all the flagrant abuses and government schemes that tried desperately to keep people separated. But seeing and experiencing that – and studying it deeply, which is what I was there to do – also allowed me to come back to my own country and finally, for the first time, see our own instituitionalized segregation. I could see how our government’s programs and policies – even those from just ten or twenty or forty years ago – had totally skewed the way we all experience the world, and though one’s experience certainly relied on many factors including gender and wealth, race was a huge one.

I was reminded of this experience during a very laughable post-election moment when I was viewing this video from a Republican poll watcher in Aurora, Colorado. He was deeply concerned about the fact that the “racial mix” at the polling station he was at skewed far darker than “the mix of people at the mall.” (!!) This, he said, was evidence of some kind of Democratic conspiracy to get more non-white people to this particular polling station.

What he failed to realize is that “these people” had been in Aurora all along – they simply didn’t move in the same spaces he did. The only time he saw them was now, on election day, when they all had to come to the same place to vote. If he hadn’t been a poll watcher, he likely would never have noticed them. Because that’s privilege. Because that’s having the ability to live in spaces that have been built to exclude others, and give you a false sense of the world.

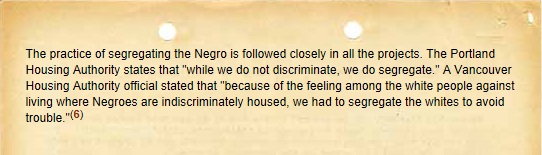

After living in Durban, I moved to Chicago, and experienced that eerie train ride from the north side of Chicago to the south side, where the composition of people on the train changes so dramatically that it looks… planned. Because it was. Planned and enforced. Just as it had been in my great-grandfather’s neighborhood in Portland, OR.

When I read a lot of golden age SF, I think about these guys who grew up in planned neighborhoods like my great-grandfather’s, where people who were “different” from the false middle-class white “norm” were excluded. I think of television shows that still give us this narrow view of what “normal” is – so very white, so very male, with strict standards on body sizes and face shapes.

If this is the world you’re fed every day, why wouldn’t you replicate it? Of course, the future is white and male and middle class. Of course the galactic empire is white and male and middle class. It is constructed that way. Just like our cities.

But no matter how many neighborhoods we gate off, or how many white faces we hand-select to deliver our media, it doesn’t change the truth. It doesn’t alter the math. Our world is a diverse and interesting one. It’s not monochrome. To pretend otherwise is to live in a bubble of self-defeating lies and denial that serves no one, and changes nothing.

So when people tell me that including “so many” non-white characters in my fiction is “political” or that I’m trying to make some kind of “statement” I can’t help but counter with the fact that the “statement” made by every writer with a white monochrome world is also deeply political, even more so because it’s based on a false sense of normal that’s been carefully and systematically constructed for hundreds of years in this country (and others).

I like to think that some folks slowly wake up to that lie, but until we succeed in desegregating the ways we live and work and actually start populating our media with an accurate representation of what our world looks like, I figure we’re still in for another fifty years of clunky – and increasingly ridiculous-looking – whitewashing.

As a creator, as a media-maker, I know I can choose to blindly perpetuate those myths, or help overturn them. But I couldn’t make that choice until I stopped eating up the lie of what the world was really like.